1×9 adjoint(::Vector{Float64}) with eltype Float64:

0.0 0.375 0.75 1.125 1.5 1.875 2.25 2.625 3.0Machine Learning for Computational Economics

Module 02: Discrete-Time Methods

EDHEC Business School

Purdue University

January 2026

Introduction

Discrete-time methods are the natural starting point for dynamic programming.

- In this module, we introduce classical numerical methods to solve such models.

- These techniques provide a natural starting point for more advanced methods.

We illustrate these concepts with a consumption-savings problem

- This model is the backbone of many applications in macroeconomics and finance.

- It is a key building block for many heterogeneous-agent models.

This benchmark problem allows us to illustrate three core computational tasks:

- Representing value and policy functions on a grid

- Computing expectations in problems with uncertainty

- Performing the maximization step efficiently

I. The Consumption-Savings Problem

A Consumption-Savings Problem

Consider a household deciding how much to consume and save when income is uncertain.

- The household enters each period with cash-on-hand \(M_t\), sum of financial wealth \(W_t\) and labor income \(Y_t\).

- The household earns a risk-free return \(R\) on her savings

Cash-on-hand evolves according to: \[ M_{t+1} = \color{#0072b2}{\underbrace{R\,(M_t - c_t)}_{\text{return on savings}}} + \color{#d55e00}{\underbrace{Y_{t+1}}_{\text{labor income}}}. \]

The household’s problem is to choose a consumption plan \(\{c_t\}_{t=0}^{T-1}\) that maximizes expected lifetime utility: \[

V_T(M)

= \max_{\{c_t\}_{t=0}^{T-1}}

\mathbb{E}\!\left[

\sum_{t=0}^{T-1} e^{-\rho t}\, u(c_t)

+ e^{-\rho T}\, \color{#009e73}{\underbrace{V_0(M_T)}_{\text{terminal payoff}}}

\right],

\]

subject to the transition equation for cash-on-hand and the stochastic process for labor income, \[

\log Y_{t+1} \sim \mathcal{N}\!\left(- \tfrac{1}{2}\sigma_y^2,\, \sigma_y^2\right),

\] where the normalization ensures that \(\mathbb{E}[Y_t] = 1\).

The Recursive Representation

The recursive problem is given by \[

V_t(M)

= \max_{c}

\left\{

u(c) + e^{-\rho} \mathbb{E}\!\left[ V_{t-1}(M') \right]

\right\},

\]

subject to \[

M' = R (M - c) + Y', \qquad

\log Y' \sim \mathcal{N}\!\left(- \tfrac{1}{2}\sigma_y^2,\, \sigma_y^2\right).

\]

Preferences and terminal payoff are of the constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) form: \[

u(c) = \frac{c^{1-\gamma}}{1-\gamma}, \qquad

V_0(M) = A \frac{M^{1-\gamma}}{1-\gamma}.

\]

where \(\gamma > 0\) is the coefficient of relative risk aversion and \(A > 0\) is a scaling parameter.

Note

The infinite-horizon problem, where \(T \to \infty\), corresponds to the stationary solution of the recursive problem. In this case, the value function satisfies the fixed-point condition \(V_t(M) = V_{t-1}(M) \equiv V(M)\).

The Action-Value Function

The action-value function is given by \[ V_t(M, c) \equiv u(c) + e^{-\rho} \mathbb{E}\!\left[ V_{t-1}(R (M- c) + Y') \right]. \]

Tip

The action-value function corresponds to the value associated with a given action (no maximization step).

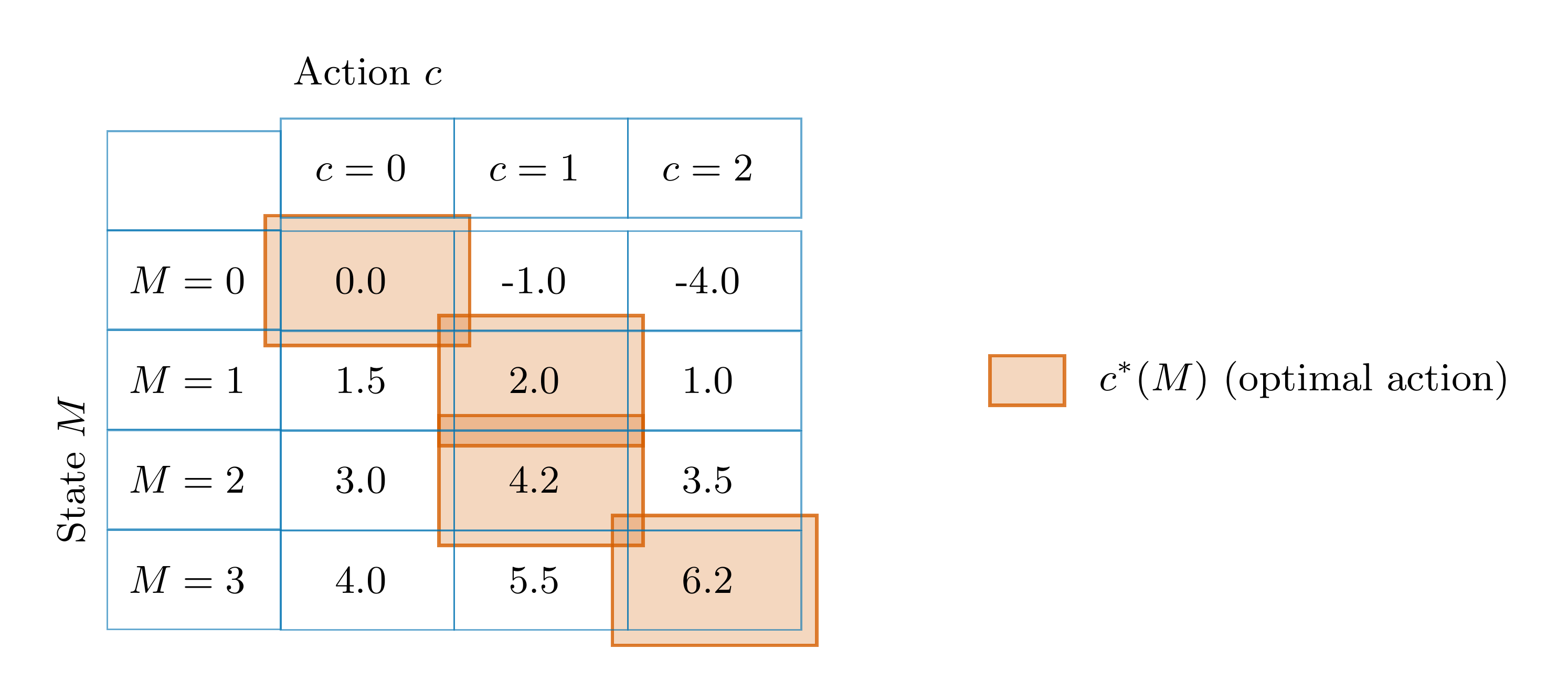

Think of \(V_t(M,c)\) as a table

- Columns: actions \(c\)

- Rows: states \(M\)

Optimal consumption: \[c_t(M) = \arg\max_{c} V_t(M,c)\]

Value Function Iteration

We can solve the Bellman equation by value function iteration (VFI).

- Given \(V^{(0)}(M)\), find the optimal consumption: \(c^{(1)}(M) = \arg\max_{c} V^{(1)}(M,c)\).

- Update the value function as \(V_1(M) = V_1(M, c_1(M))\).

Algorithm: Value Function Iteration (VFI)

Input: Initial guess \(V^{(0)}(M)\), tolerance tol

Output: Value \(V(M)\), policy \(c^*(M)\)

Initialize: \(t \gets 0\)

Repeat until \(\|V^{(t+1)}-V^{(t)}\|_\infty < \texttt{tol}\):

Policy update: \[c_{t+1}(M) \gets \arg\max_{c}\left\{ u(c) + e^{-\rho}\,\mathbb{E}[V_{t}(R(M-c)+Y')] \right\}\]

Value update: \[V_{t+1}(M) \gets u(c_{t+1}(M)) + e^{-\rho}\,\mathbb{E}\left[ V_{t}(R(M-c_{t+1}(M))+Y') \right]\]

\(t \gets t+1\)

Return: \(V^{(t)},\,c^{(t)}\)

II. Numerical Solution

Numerical Solution

There is no known analytical solution to this problem.

- We must then resort to numerical methods.

To solve the problem numerically, we must overcome three main challenges:

- Represent the value function in the computer

- Compute expectations in problems with uncertainty

- Perform the maximization step efficiently

Representing the Value Function

We need to find a way to represent the value function in the computer.

- We need a finite representation of an infinite-dimensional object.

- In our single-state problem, this can be done by representing the value function on a grid.

We begin by constructing a finite grid for \(M\): \[ M \in \mathcal{M} = \{M_{1}, M_{2}, \ldots, M_{N}\}. \]

At each point on this grid, we store the corresponding value function as a vector: \[ \mathbf{V}_t = (V_{t,1}, V_{t,2}, \ldots, V_{t,N})^\top, \qquad \text{where } V_{t,i} \equiv V_t(M_i). \]

Similarly, the optimal consumption policy can be represented as a vector: \[ \mathbf{c}_t = (c_{t,1}, c_{t,2}, \ldots, c_{t,N})^\top, \qquad \text{where } c_{t,i} \equiv c_t(M_i). \]

Interpolating the Value Function

Suppose we start with the initial value function represented on a grid: \(\mathbf{V}_0\).

- To compute \(\mathbb{E}[V_0(R(M-c)+Y')]\), we need to evaluate the value function at points outside the grid.

- We can use linear interpolation to approximate the value function between grid points.

For \(M \in [M_{i-1}, M_i]\), we assume that \(V_t(M)\) is linear and approximate it as \[ V_t(M) \approx \frac{M - M_{i-1}}{M_i - M_{i-1}}\, V_{t,i} + \frac{M_i - M}{M_i - M_{i-1}}\, V_{t,i-1}. \]

We can implement linear interpolation using the Interpolations.jl package.

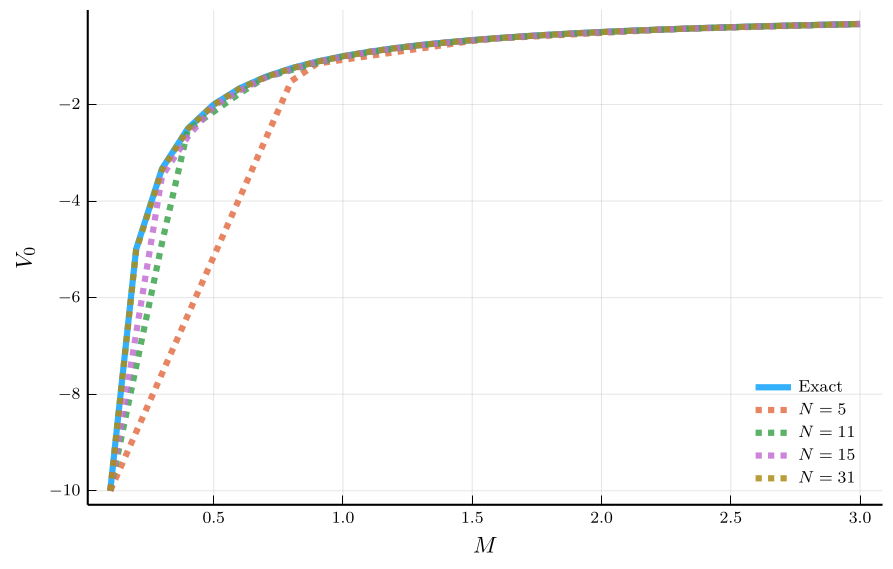

Accuracy of a Linear Interpolation

The accuracy of a linear interpolation depends on the grid size.

- We can approximate even very non-linear functions this way.

- Depending on the function, this may require a very fine grid.

Quality of approximation may not be uniform

- Worse approximation near the boundaries.

Uniform grid can be very inefficient

- It does not allow to focus where it is needed

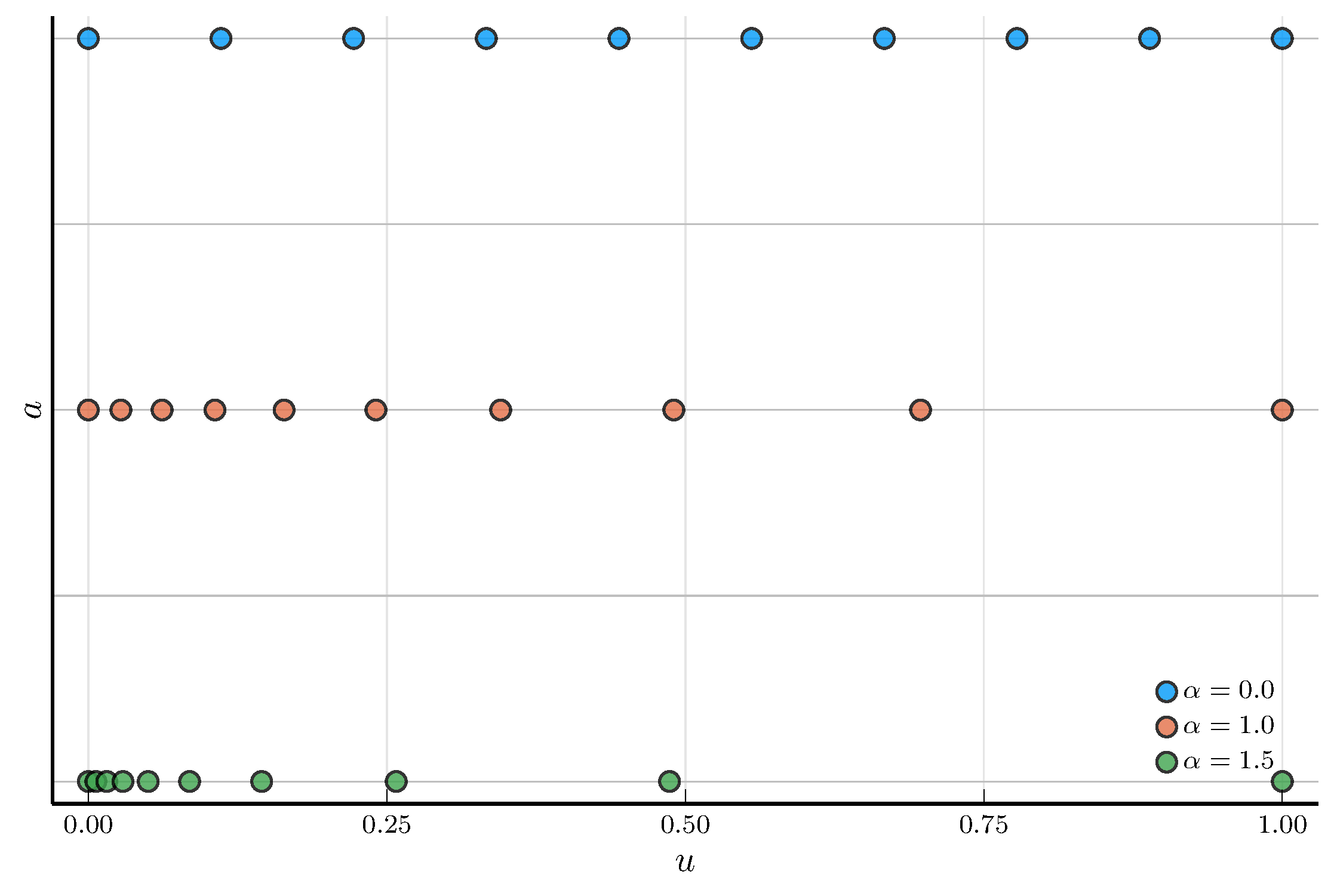

Non-Uniform Grids

An alternative is to use a non-uniform grid for the state variable.

A convenient choice is the double-exponential grid

- Clusters grid points near the lower bound.

- Let \(u^j\) denote a uniform grid on the unit interval \([0,1]\).

- Define the grid points as \[ a_j = a_{\min} + (a_{\max} - a_{\min}) \frac{e^{\,e^{\alpha u^j}-1} - 1}{e^{\,e^{\alpha}-1} - 1}, \]

The parameter \(\alpha > 0\) controls the degree of clustering.

- As \(\alpha \to 0\), the grid becomes approximately uniform.

- For large \(\alpha\), the grid is very dense near the lower bound.

We can implement this in Julia as follows:

Computing Expectations

The second issue we must address is how to compute expectations.

- In our setting, this amounts to integrating over the stochastic labor income \(Y'\).

The expectation in the Bellman equation can be written as the integral: \[ \mathbb{E}\!\left[V_{t}(M')\right] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} V_t(R(M - c_t(M)) + e^{y'}) \phi(y') d y', \] where \(\phi(y')\) is the probability density function of a normal random variable.

Computing this expectation numerically requires approximating the integral.

- A common approach is to discretize the process for the log income \(y_t \equiv \log Y_t\)

- We replace the continuous process by a finite-state Markov chain.

- Next: construct a grid and transition probabilities for the Markov chain.

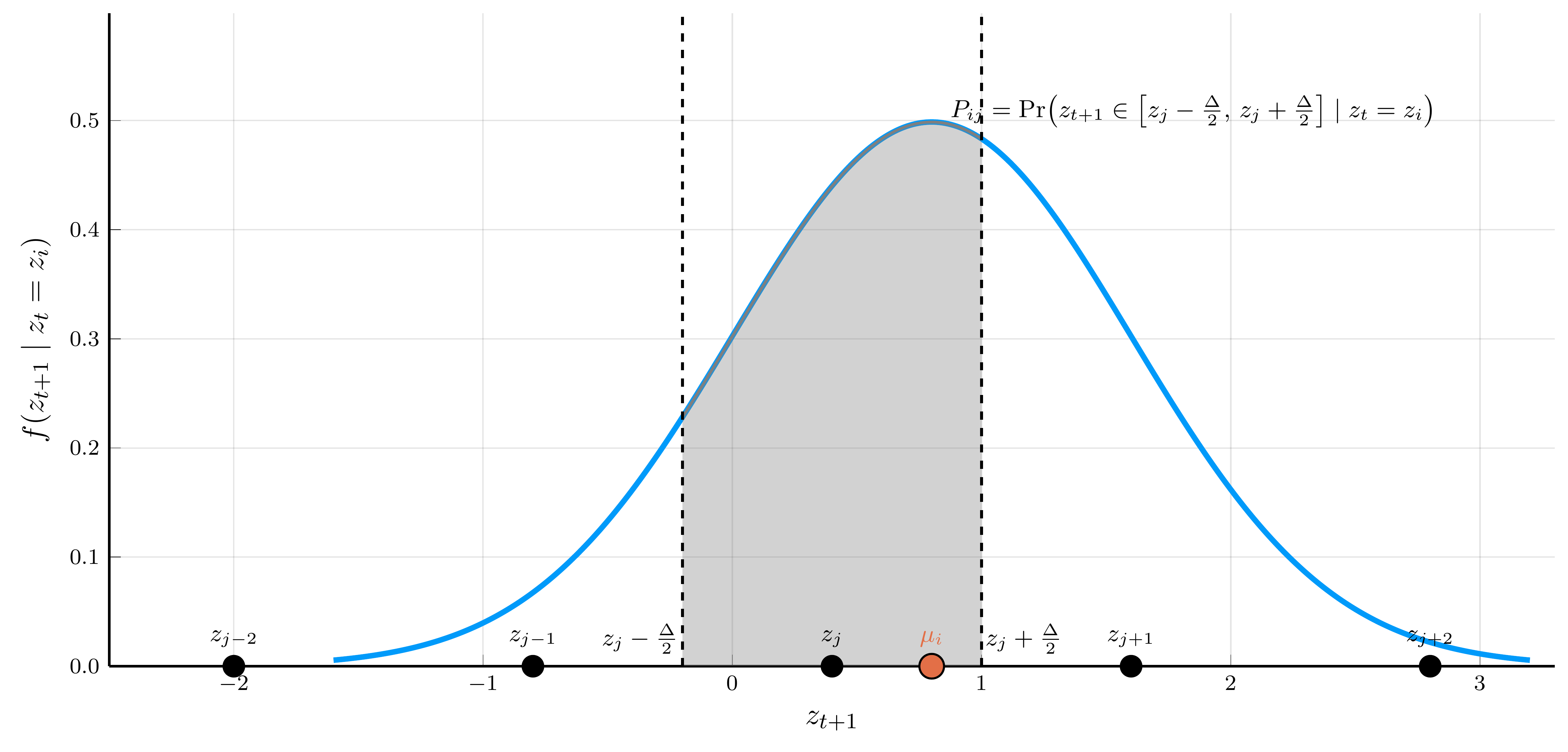

The Tauchen Method: Constructing the Grid

The Tauchen method is a common approach to discretize the process for an AR(1) process: \[ z_{t+1} = \mu + \rho_z (z_t - \mu) + \varepsilon_{t+1}, \qquad \varepsilon_{t+1} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_\varepsilon^2), \] where \(|\rho_z| < 1\) and \(\sigma_\varepsilon > 0\) (in our case, \(\rho_z = 0\) and \(\sigma_\varepsilon = \sigma_y\)).

We start by constructing an uniform grid \[ z \in \mathcal{Z} = \{z_1, z_2, \ldots, z_{N_z}\}, \] with step size \(\Delta = \frac{z_{N_z} - z_1}{N_z - 1}\).

A convenient choice for the endpoints is \[ z_1 = \mu - m\,\frac{\sigma_z}{\sqrt{1 - \rho_z^2}}, \qquad z_{N_z} = \mu + m\,\frac{\sigma_z}{\sqrt{1 - \rho_z^2}}, \] where \(m\) is typically set to \(3\), ensuring that the grid spans \(\pm3\) unconditional standard deviations of \(z_t\).

The Tauchen Method: Computing the Transition Probabilities

We need to determine the transition probabilities \(P_{ij} = \Pr(z_{t+1} = z_j \mid z_t = z_i)\).

- Conditional on \(z_t = z_i\), we have that \(z_{t+1} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu + \rho_z (z_i - \mu), \sigma_\varepsilon^2\right)\).

The transition probability \(P_{ij}\) equals the probability that \(z_{t+1}\) falls between the midpoints surrounding \(z_j\):

\[\scriptsize P_{ij} = \begin{cases} \Phi\!\left(\dfrac{z_j - \mu_i + \tfrac{\Delta}{2}}{\sigma_\varepsilon}\right), & j = 1, \\[0.75em] \Phi\!\left(\dfrac{z_j - \mu_i + \tfrac{\Delta}{2}}{\sigma_\varepsilon}\right) - \Phi\!\left(\dfrac{z_j - \mu_i - \tfrac{\Delta}{2}}{\sigma_\varepsilon}\right), & 1 < j < N_z, \\[0.75em] 1 - \Phi\!\left(\dfrac{z_j - \mu_i - \tfrac{\Delta}{2}}{\sigma_\varepsilon}\right), & j = N_z, \end{cases} \]

The Tauchen Method in Julia

"""

Tauchen (1986) discretization of the AR(1) process

z_{t+1} = μ + ρ z_t + ε_{t+1}, ε ~ N(0, σϵ^2).

"""

function tauchen(M::Int, ρ::Real, σϵ::Real; μ::Real=0.0, m::Real=3.0)

@assert M ≥ 2 "Need at least M=2 grid points."

@assert abs(ρ) < 1 "Require |ρ|<1 for stationary AR(1)."

σz = σϵ / sqrt(1 - ρ^2) # unconditional std. dev.

z̄ = μ / (1 - ρ) # unconditional mean

if σϵ == 0.0 return (; z = [z̄], P = [1.0]) end # degenerate case

zmin, zmax = z̄ - m*σz, z̄ + m*σz

Δ = (zmax - zmin) / (M - 1)

z = collect(range(zmin, zmax, length=M))

P = zeros(Float64, M, M)

for i in 1:M

mean_next = μ + ρ*z[i]

dist = Normal(mean_next, σϵ)

# First bin: (−∞, midpoint_1]

P[i, 1] = cdf(dist, z[1] + Δ/2)

# Interior bins: (midpoint_{j-1}, midpoint_j]

for j in 2:M-1

upper = z[j] + Δ/2

lower = z[j] - Δ/2

P[i, j] = cdf(dist, upper) - cdf(dist, lower)

end

# Last bin: (midpoint_{N-1}, +∞)

P[i, M] = 1 - cdf(dist, z[M] - Δ/2)

end

return (;z, P)

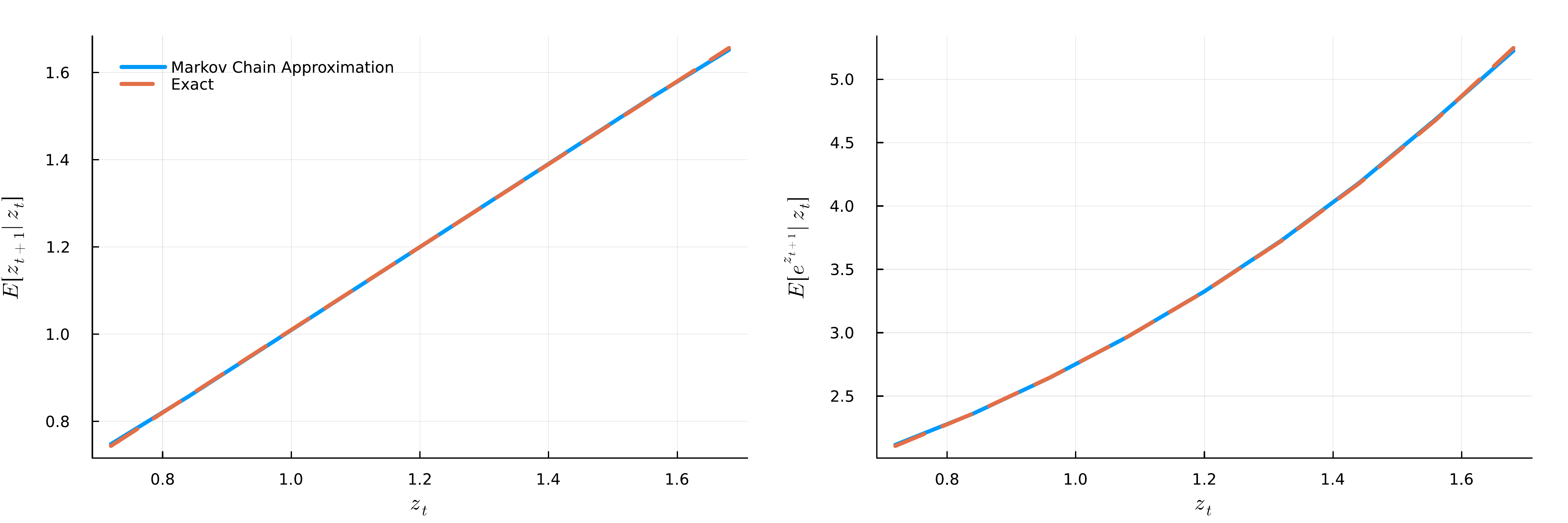

end;Conditional Moments: Exact vs. Markov Chain Approximation

The optimization step

The third issue we must address is how to perform the maximization step efficiently.

A direct approach is to specify a grid for the control variable \(c \in \mathcal{C} = \{c_1, c_2, \ldots, c_{N_c}\}\)

The optimal consumption is given by \(c_t(M) = \arg\max_{c} V_t(M, c)\).

This brute-force approach can be computationally expensive

- An alternative is to use the first-order condition and envelope condition:

\[ \color{#0072b2}{\underbrace{u'(c_t(M)) = e^{-\rho} R \sum_{j=1}^{N_y} P_j\, V_{t-1}'\!\left(R (M - c_t(M)) + Y'_j\right)}_{\text{first-order condition}}} , \qquad \qquad \color{#d55e00}{\underbrace{V_{t}'(M) = u'(c_{t}(M))}_{\text{envelope condition}}} \]

Combining the two conditions, we obtain the consumption Euler equation: \[ u'(c_t(M)) = e^{-\rho} R \sum_{j=1}^{N_y} P_j\, u'\!\left(c_{t-1}\!\left(R (M - c_t(M)) + Y'_j\right)\right). \]

To obtain \(c_t(M)\), we need to solve a nonlinear equation for each \(M\).

The Endogenous Gridpoint Method

Carroll (2006) proposed the endogenous gridpoint method (EGM) that avoids the root-finding step:

- Define a grid for the end-of-period assets \(a_t(M) \equiv M - c_t(M)\): \[ a_t(M) \in \mathcal{A} = \{a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_{N_a}\} \]

- Solve for consumption inverting the consumption Euler equation: \[ c_{t,i} = u'^{-1}\!\left( e^{-\rho} R \sum_{j=1}^{N_y} P_j\, u'\!\left(c_{t-1}\!\left(R a_i + Y'_j\right)\right) \right). \]

- Interpolate the new policy function over the endogenous grid: \[ M_{t,i} = a_i + c_{t,i}. \]

- Update the value function: \[ V_t(M) = u(c_t(M)) + e^{-\rho} \sum_{j=1}^{N_y} P_j\, V_{t-1}\!\left(R (M - c_t(M)) + Y'_j\right). \]

III. Julia Implementation

Model Struct

We have seen how to represent the value function, compute expectations, and perform the maximization step.

- We are now ready to solve for the value and policy functions.

- To make the implementation modular and reusable, we encapsulate all parameters and grids in a Julia struct.

Base.@kwdef struct ConsumptionSavingsDT

γ::Float64 = 2.0 # CRRA coefficient

ρ::Float64 = 0.05 # discount rate

A::Float64 = 1.00 # terminal value function parameter

R::Float64 = exp(ρ) # interest rate

σ::Float64 = 0.25 # standard deviation of log income

Z::NamedTuple = tauchen(9, 0.0, σ) # income process

Y::Vector{Float64} = exp.(Z.z) # income levels

N::Int64 = 11 # number of grid points

α::Float64 = 0.0 # grid spacing parameter

Mgrid::Vector{Float64} = make_grid(0.0, 2.5, N; α = α)

agrid::Vector{Float64} = make_grid(0.0, 1.0, N; α = α)

endThe struct stores the parameters and grids for the model.

- This lets us pass the entire model cleanly between solvers, simulators, and calibration routines

- Makes it easy to override the baseline calibration via keyword arguments

Risk aversion in model 1: 2.0 | Discount rate in model 1: 0.05

Risk aversion in model 2: 1.5 | Discount rate in model 2: 0.05One-step Value Function Iteration

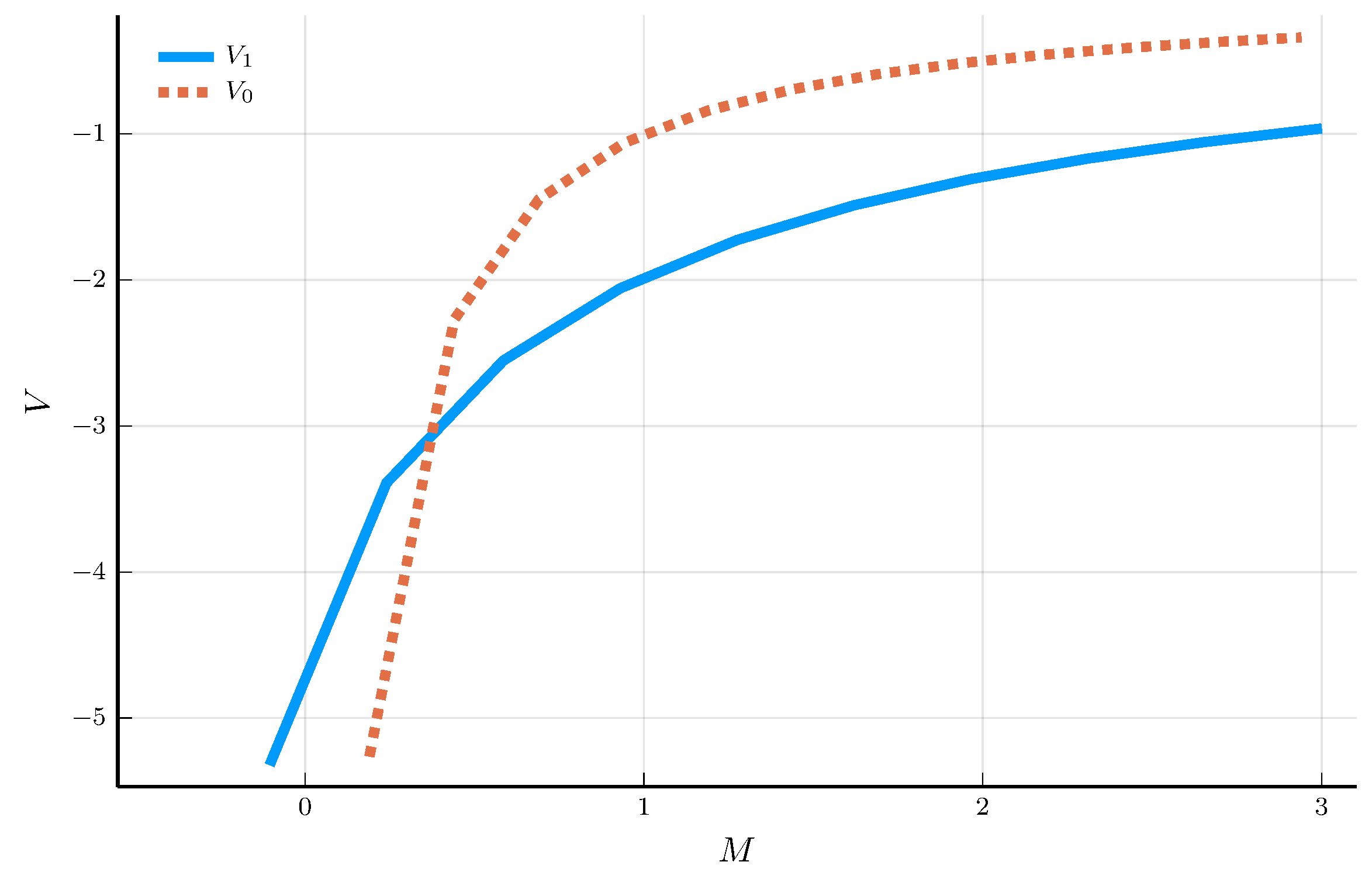

We now solve for \(V_1(M)\) and \(c_1(M)\), given the terminal condition \(V_0(M) = \frac{M^{1-\gamma}}{1-\gamma}\).

- We start with the brute-force approach.

- We discretize the control space into \(N_c\) points and choose the maximizer of the action-value function.

We need to specify the admissible consumption set.

- The lower bound is naturally \(c=0\).

- For the upper bound, feasibility requires that next period’s cash-on-hand be nonnegative for all realizations of \(Y'\): \[ c_{\max}(M) = M + \frac{Y_{\min}}{R}, \] since choosing \(c=c_{\max}(M)\) leaves \(M' = R(M-c) + Y_{\min} = 0\) next period.

function vf_iteration(m::ConsumptionSavingsDT, V0::Function; NM::Int64 = 11, Nc::Int64 = 101)

(; Y, Z, R, γ, ρ) = m # unpack model parameters

Mgrid = collect(range(-Y[1]/R, 3.0, length=NM)) # grid for M

cgrid = [range(0.0, m + Y[1]/R, length=Nc) for m in Mgrid] # collection of grids for c

# Action-value function

V1(M, c) = c^(1-γ)/(1-γ) + exp(-ρ) * sum(Z.P[1,j] * V0(m,R * (M-c) + Y[j]+1e-12) for j in eachindex(Y))

# Policy and value functions

C = [cgrid[j][argmax([V1(Mgrid[j], c) for c in cgrid[j]])] for j in eachindex(Mgrid)]

V = [V1(Mgrid[j], C[j]) for j in eachindex(Mgrid)]

return (; C, V, Mgrid) # return a named tuple

endPolicy and Value Functions

Two theoretical bounds for the policy function:

Lower bound: household receives the lowest income with certainty.

Upper bound: household receives the average income with certainty.

a) Policy functions

b) Value functions

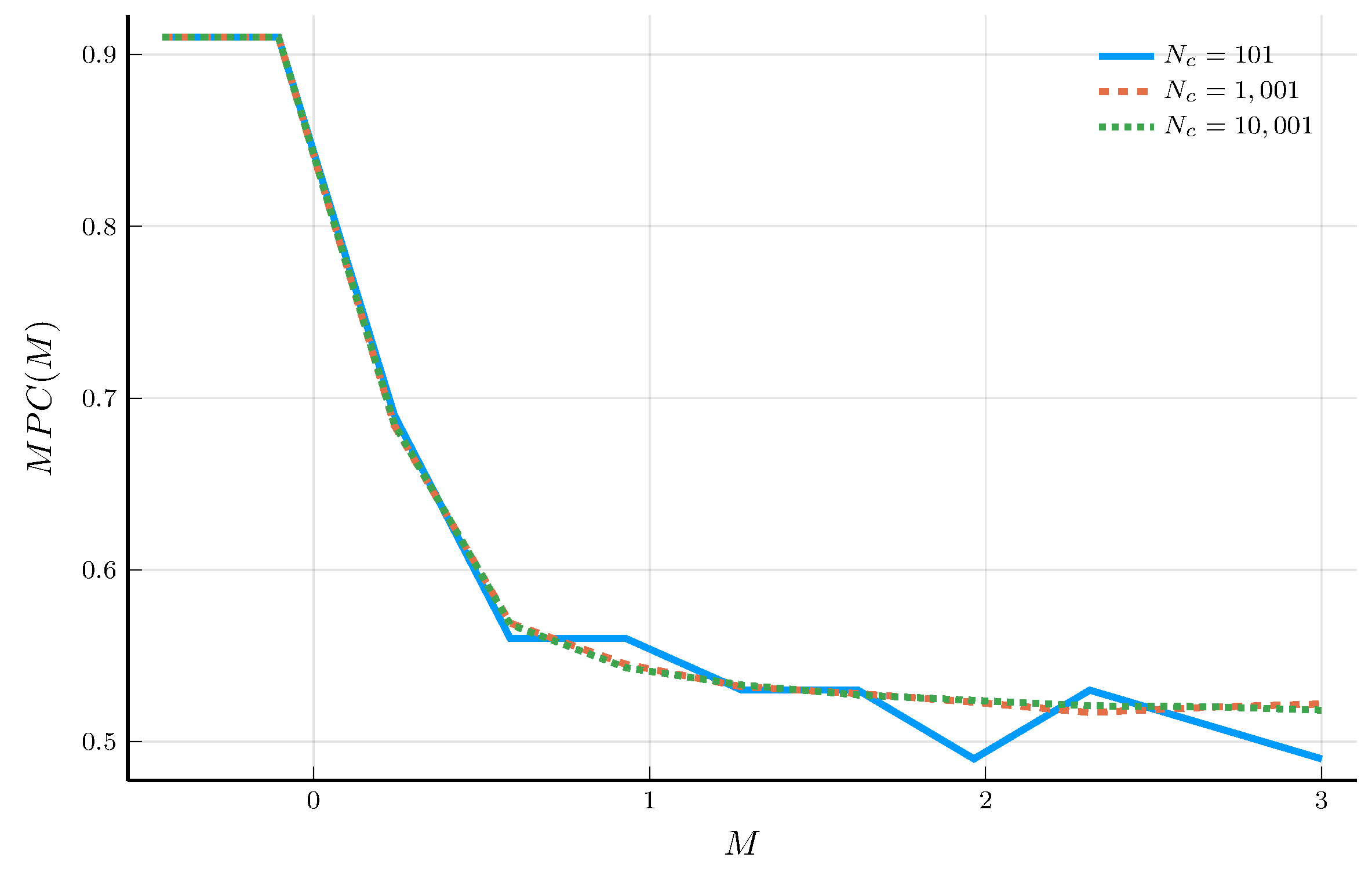

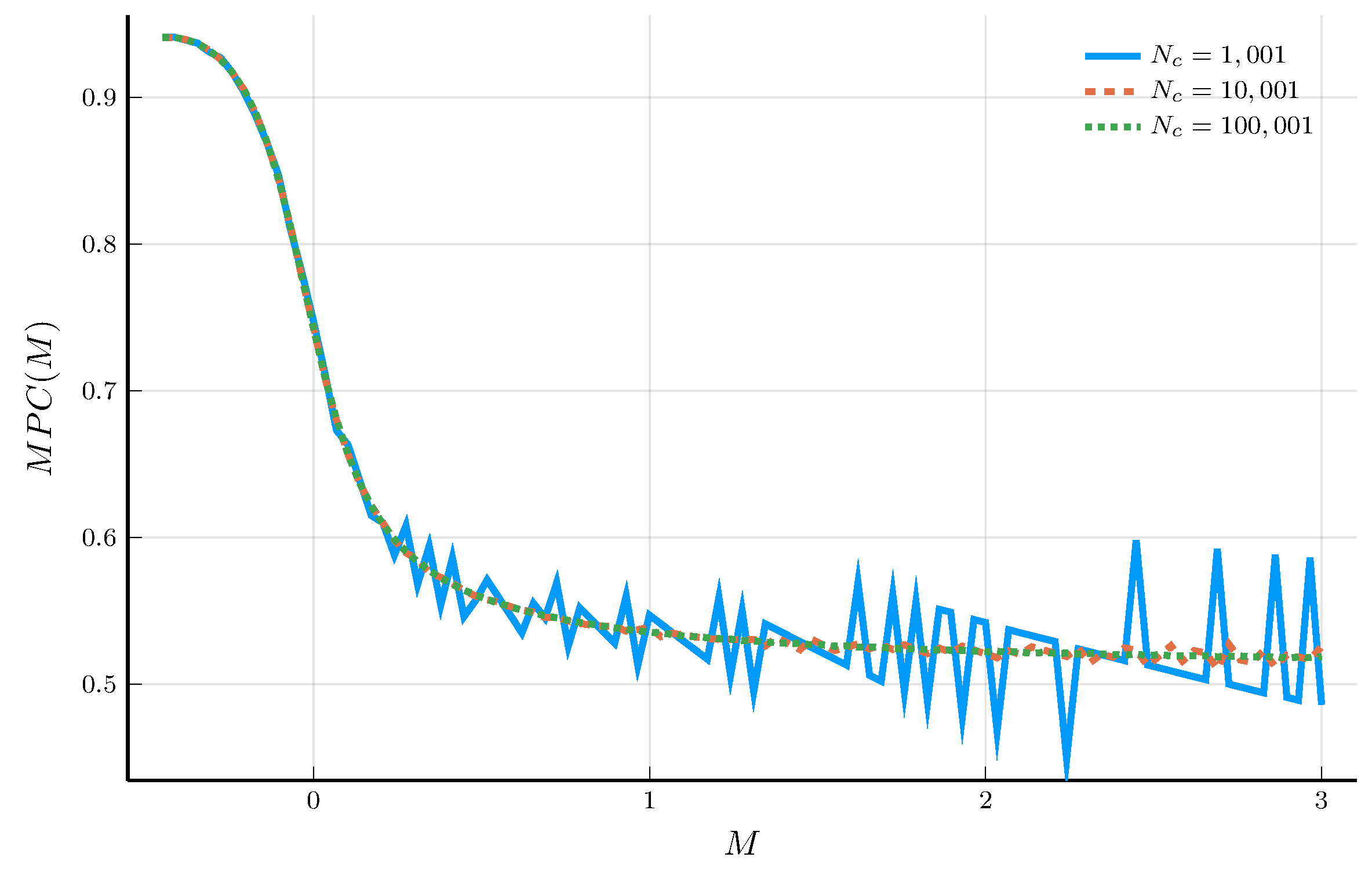

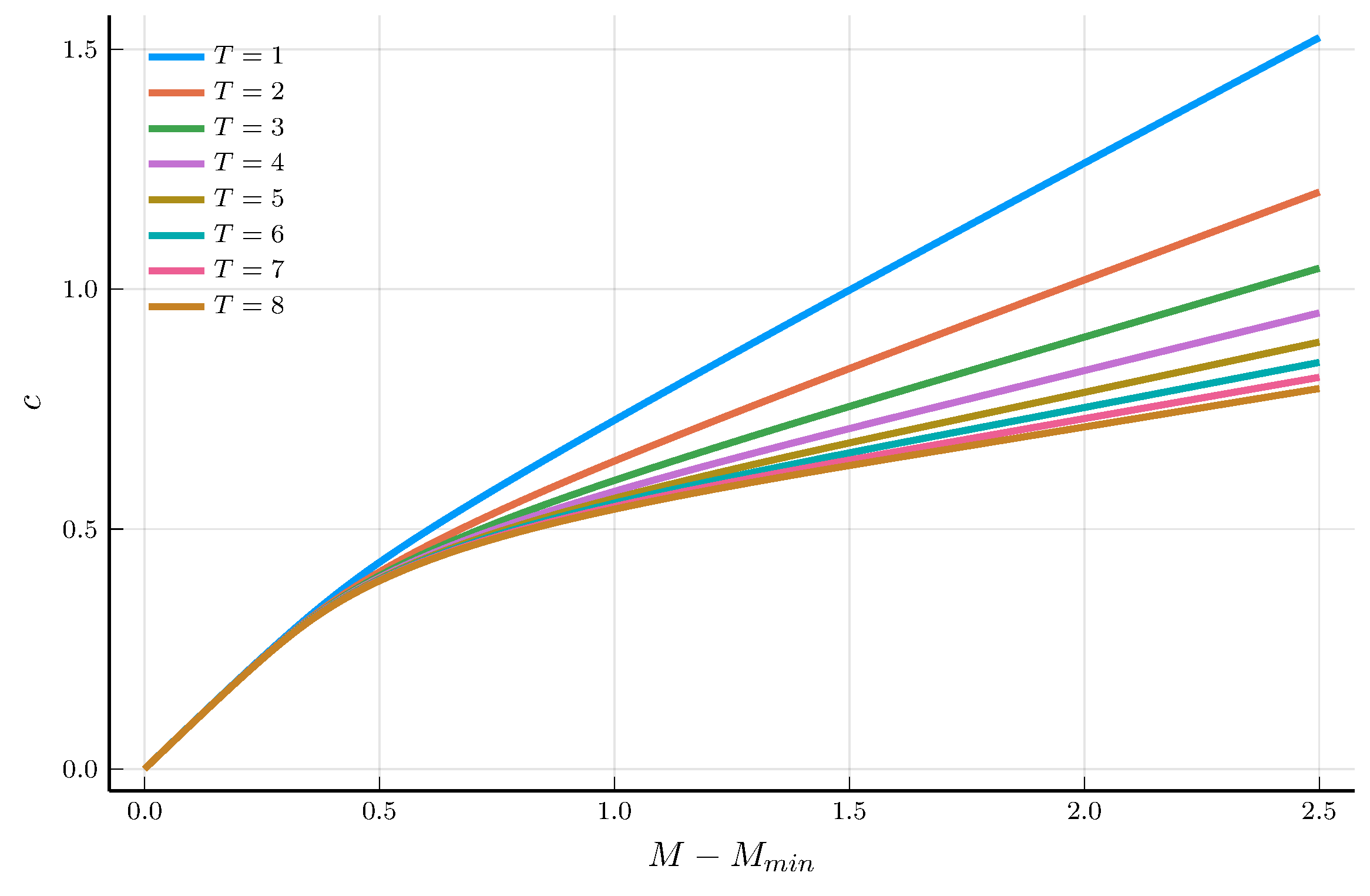

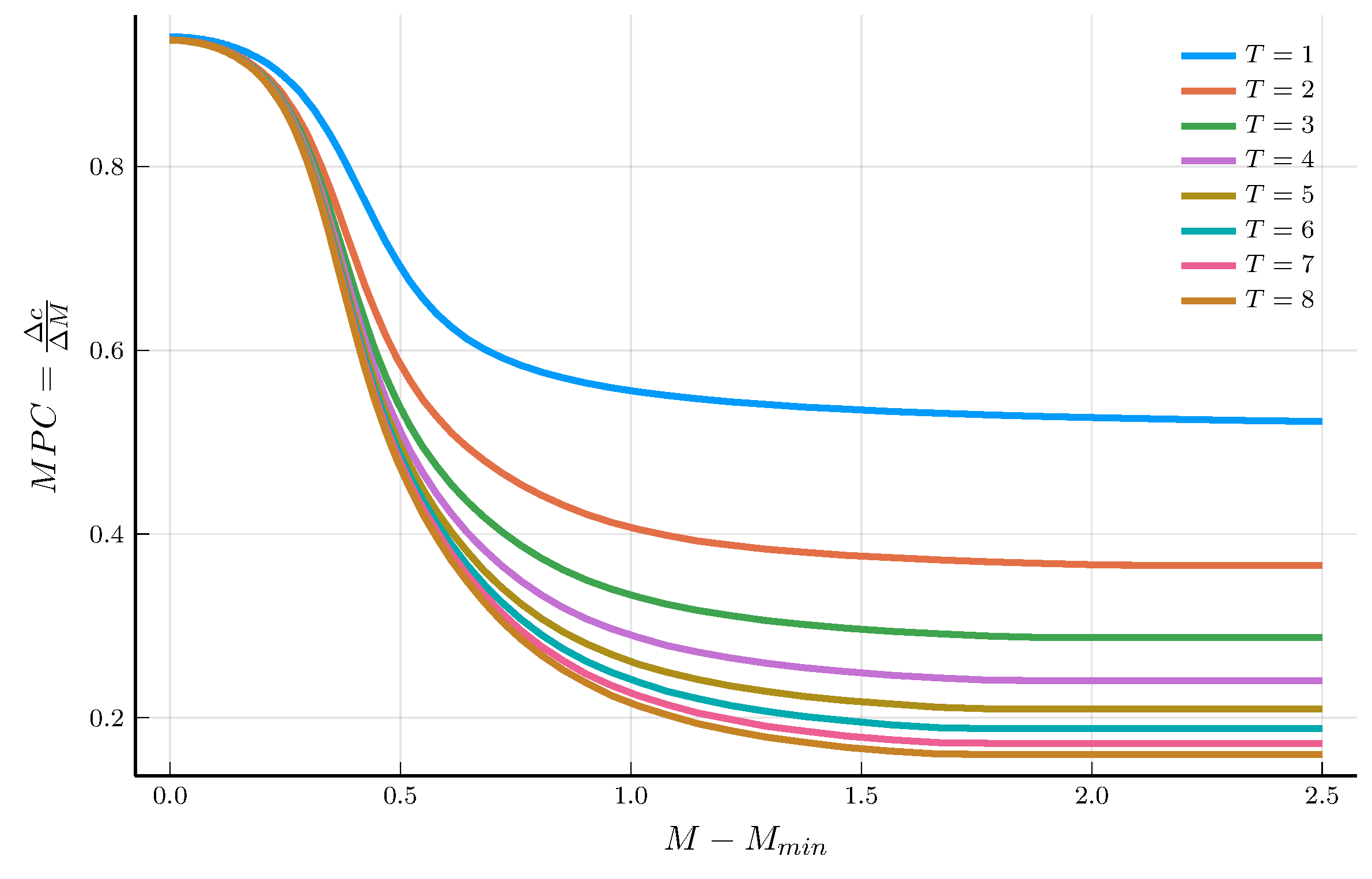

The Marginal Propensity to Consume

Given the policy function \(c_t(M)\), we can obtain the marginal propensity to consume (MPC).

- The MPC measures the change in consumption for a change in \(M\): \(MPC(M) = \frac{d c_t(M)}{d M}\).

Carroll and Kimball (1996) show that the MPC is decreasing in \(M\).

- But the numerical solution does not necessarily satisfy this property.

a) MPCs for \(N_M = 11\)

b) MPCs for \(N_M = 101\)

The EGM Step

We now solve for the value and policy functions using the endogenous gridpoint method (EGM).

This approaches approximates the policy function directly, rather than the value function.

We focus on the case the household can borrow up to the natural borrowing limit.

The limit varies with the horizon: \(a_T(M) \geq \underline{a}_T\): \[ \underline{a}_T = -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \frac{Y_{\min}}{R^t}. \]

We work with the transformed grid: \[ \tilde{a}_t(M) = a_t(M) - \underline{a}_t, \]

function egm_step(m::ConsumptionSavingsDT, iter::Int, c0::Function)

(; agrid, Z, Y, R, γ, ρ) = m # unpack model parameters

agrid_shifted = -Y[1] * sum(R.^(-(1:iter))) .+ agrid

# compute the consumption policy

c1 = [sum(exp(-ρ) * Z.P[1,j] * R * c0(R * a + Y[j]+1e-12)^(-γ)

for j in eachindex(Y))^(-1/γ) for a in agrid_shifted]

M1 = agrid_shifted .+ c1 # compute the cash-on-hand

return (; c = linear_interpolation(M1, c1;

extrapolation_bc=Line()), M = M1)

endThe EGM Iteration

We iterate the EGM step until the policy function converges.

We can compute the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) using the finite-difference method.

a) Policy function

b) Marginal propensity to consume

IV. The Challenge of High-Dimensional Problems

The Three Curses of Dimensionality Revisited

The methods discussed in this module are the backbone of modern computational economics.

- They are very effective in one or two dimensions.

- However, they suffer from the three curses of dimensionality.

1) The curse of representation

- We represented the value and policy functions on a grid.

- The number of grid points grows exponentially with the number of state variables.

2) The curse of optimization

- The EGM method enable us to avoid the costly root-finding step with a single control variable.

- But this only works seamlessly in the case of a single control variable.

3) The curse of expectation

- We computed expectations using the Tauchen method.

- The Markov chain approximation becomes increasingly costly with more shocks

The Way Forward

The techniques discussed in this module suffer from the three curses of dimensionality.

- Overcoming these limitations requires new tools.

We will rely on a combination of two main ingredients:

- Continuous-time methods combined with machine learning techniques.

Before jumping into machine learning, we discuss next continuous-time methods.